Topics so far –

Now –

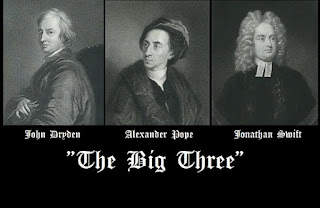

14. The Age of Classicism

Next –

15. The Transition Age

16. The Romantic Age

The Age of Classicism – 1702 to 1740

The literary

career of Pope forms the axis of this age. One might therefore consider it as

roughly ending a few years before his death, about 1740. From 1702 to 1740

there reigns the relative unity of a literary age. Its general traits originate

in those of the Restoration, which they continue, accentuate and also in

reaction modify.

The Classical School of Poetry: Pope

Alexander Pope was, like Dryden after 1685,

a Catholic, and therefore an outsider in the Protestant-dominated society of

the early eighteenth century. The two men were, however, of totally different

generations and background. Pope was 12 when Dryden died, and was suffering

from the spinal disease which left him deformed and sickly for the rest of his life.

Pope had, in common with Dryden,

considerable success in translating Greek and Latin classics – especially Homer

– into English, and also prepared a noted, if flawed, edition of Shakespeare,

in 1725. But he never engaged in serious political, philosophical, and

religious debate on the scale that Dryden achieved. Perhaps because of his poor

health, Pope was something of a recluse, but he was very involved in high

society, and took sides on most of the political issues of his day. His satires

are full of savage invective against real or imagined enemies. Pope’s sphere

was social and intellectual. The Rape of the Lock (1712–14), written when he was in his mid-twenties, is the

essence of the mock heroic. It makes a family quarrel, over a lock of hair, into

the subject of a playful poem full of paradoxes and witty observations on the

self-regarding world it depicts, as the stolen lock is transported to the heavens

to become a new star. ‘Fair tresses man’s imperial race insnare’ makes

Belinda’s hair an

Pope had, in common with Dryden,

considerable success in translating Greek and Latin classics – especially Homer

– into English, and also prepared a noted, if flawed, edition of Shakespeare,

in 1725. But he never engaged in serious political, philosophical, and

religious debate on the scale that Dryden achieved. Perhaps because of his poor

health, Pope was something of a recluse, but he was very involved in high

society, and took sides on most of the political issues of his day. His satires

are full of savage invective against real or imagined enemies. Pope’s sphere

was social and intellectual. The Rape of the Lock (1712–14), written when he was in his mid-twenties, is the

essence of the mock heroic. It makes a family quarrel, over a lock of hair, into

the subject of a playful poem full of paradoxes and witty observations on the

self-regarding world it depicts, as the stolen lock is transported to the heavens

to become a new star. ‘Fair tresses man’s imperial race insnare’ makes

Belinda’s hair an

attractive trap for all

mankind – a linking of the trivial with the apparently serious, which is Pope’s

most frequent device in puncturing his targets’ self-importance.

The Dunciad (1726,

expanded in 1743) is Pope’s best-known satire. It is again mock heroic in

style, and, like Dryden’s MacFlecknoe some fifty years before, it is an

attack on the author’s literary rivals, critics, and enemies. Pope groups them

together as the general enemy ‘Dulness’, which gradually takes over the world,

and reduces it to chaos and darkness.

Pope’s intentions in his writing were wide-ranging.

His Moral Essays from the 1730s, his An Epistle to Doctor Arbuthnot (1735),

his An Essay on Man (1733–34), and the early Essay on Criticism (1711)

explore the whole question of man’s place in the universe, and his moral and

social responsibilities in the world.

A little learning is a dangerous thing. (Essay

on Criticism)

True wit is nature to advantage dressed,

What oft was thought but ne’er so well

expressed.

(Essay on Criticism)

True ease in writing comes from art, not

chance,

As those move easiest who have learned to

dance.

’Tis not enough no harshness gives offence,

The sound must seem an echo to the sense.

(Essay on

Criticism)

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan;

The proper study of mankind is man.

(An Essay on

Man)

The Imitations of Horace (1733–38)

raises issues of political neutrality, partisanship and moral satire, and as

such are a key text of the Augustan age. The conclusion of An Essay on Man,

‘Whatever is, is right’, may seem sadly banal; but a great many of Pope’s lines

are among the most memorable and quotable from English poetry. His technical

ability and wit, although firmly based in the neoclassical spirit of the time,

raised Pope’s achievement to considerable heights.

Pope in Literary Context

Pope and Neoclassicism: Pope, particularly in An Essay on Criticism and ‘‘Epistle to Arbuthnot,’’ contributed to neoclassicism, or

the resurgence in ancient ideals in art and literature—particularly the ideals

of ancient Greece and Rome. For Pope, the core truth is whatever has lasted

longest across many generations of readers; thus we should look to ancient

literature for truth. In the epics of Homer, for example, the ethics of

heroism, loyalty, and leadership are as true now as they were then. In

addition, the balanced and symmetrical structures of classical literature and

architecture represent values of reason and coherence that Pope says should

remain central to all modern arts.

Comic Satire: Pope used his great knowledge of and respect for classical

literature to write mock-epics that poked fun at the elite. Essentially Pope

believed the upper class possessed an exaggerated sense of its own importance. He

also made fun of hack writers, comparing their shoddy work with timeless

stories of the past. Pope is credited for proclaiming, ‘‘Praise undeserved is

satire in disguise.’’

Pope and Proverbs: Pope’s style and personal philosophies have become part of the

English language. For example, ‘‘A little learning is a dang’rous thing’’ comes

from An Essay on

Criticism, as

does ‘‘To err is human, to forgive, divine.’’ Other well-known sayings from An Essay on Criticism include ‘‘For fools rush in where angels

fear to tread’’ and ‘‘Hope springs eternal.’’

Literary Criticism:-

At ev’ry word a reputation dies

(Alexander Pope, The

Rape of the Lock)

Criticism, or writing about books and their

authors, is as old as writing itself. It is thus hardly surprising that the

century which saw the greatest expansion in writing and reading should also see

the arrival of the professional critic. Critical essays on theory and form,

such as Dryden’s Of Dramatic Poesy (1668), or satirical views of the

literary world, such as Swift’s The Battle of the Books (1697; published

1704 – the battle is between ancient and modern, or between classical and

contemporary literature), draw lines between older and newer styles and modes

of writing. This is criticism as an aid to the definition and aims of

literature. Under the influence of the French writer Nicholas Boileau’s Art

Poétique (1674), criticism in the Augustan age established canons of taste and

defined principles of composition and criticism.

This mix of scientific rigour and

subjective reaction has remained constant through succeeding generations. Criticism changes

almost as much as literature varies, if more slowly, but it can exert very

strong influences. And no critic is ever right, at least for any longer than

the critical fashion lasts. What is of interest is how much critical writing is

of continuing value and influence.

The Criticism of Manners:

Satire, Comedy, Memoirs – Ambrose Philips, Mary Wortley Montagu, John Arbuthnot, Swift

Ambrose Philips: He

was a friend of Pope until his Pastorals

appeared with Pope's in Tonson's Miscellany (1709).

Stung by the praise lavished on Philips, the latter published a skilfully

satirical 'eulogy' of his poems which mercilessly exposed their shortcomings.

The quarrel which followed led Pope to immortalize Philips in The Dunciad and

others of his works. Philips obtained several posts under the Government, and

passed a happy and prosperous life. He wrote three tragedies, the best of which

is The Distressed Mother (1712). He produced a fair amount of prose for the

periodicals, and his miscellaneous verse, of a light and agreeable kind, was

popular in its day. His poetry was called 'namby-pamby,' from his Christian

name; and the word has survived in its general application.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: Famous in her day for her masculine force of character, was the

eldest daughter of the Duke of Kingston. In 1712 she married Edward Wortley

Montagu, and moved in the highest literary and social circles. In 1716 her

husband was appointed ambassador at Constantinople, and while she was in the

East she corresponded regularly with many friends, both literary and personal.

She is the precursor of the great letter-writers of the later portion of the

century. Her Letters are written shrewdly and sensibly, often with a frankness that

is a little staggering. She had a vivid interest in her world, and she can

communicate her interest to her reader.

John Arbuthnot: He became acquainted with Pope and Swift. His writings are chiefly political, and

include the Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus (1709), which, though published (1741) in the works of Pope,

is thought to be his; The History of John Bull (1712 or 1713), ridiculing the war-policy of the Whigs; and The Art of Political Lying (1712).

Arbuthnot writes with wit and vivacity,

and with many pointed allusions. At his best he somewhat resembles Swift,

though he lacks the great devouring flame of the latter's personality.

Jonathan Swift: Swift is the foremost prose satirist in the

English language. His greatest satire, Gulliver’s

Travels (1726), is alternately described as an

attack on humanity and a clear-eyed assessment of human strengths and

weaknesses. In addition to his work as a satirist, Swift was also an

accomplished minor poet, a master of political journalism, a prominent

political figure, and one of the most distinguished leaders of the Anglican

church in Ireland. For these reasons he is considered one of the representative

figures of his age.

In

England, Swift secured a position as secretary to Sir William Temple, a scholar

and former member of Parliament engaged in writing his memoirs. Except for two

trips to Ireland, Swift remained in Temple’s employ and lived at his home, Moor

Park, until Temple’s death in 1699. During this period, Swift read widely, was

introduced to many prominent individuals in Temple’s circle, and began a career

in the Anglican church, an ambition thwarted by Temple’s inaction in obtaining

Swift a promised preferment in the church.

Around

this time, he met Esther Johnson, stepdaughter of Temple’s steward. ‘‘Stella,’’

as Swift nicknamed her, became an intimate, lifelong confidante to Swift.

Despite rumors to the contrary, their relationship remained platonic; Swift’s

correspondence with he was later collected in The Journal to

Stella (1963).

Toward

the end of this period, Swift wrote his first great satires, A

Tale of a Tub and The Battle of

the Books. Both were completed by 1699 but were not published until 1704

under the title A Tale of a Tub, Written for the Universal

Improvement of Mankind, to which is Added an Account of a Battel between the

Antient and Modern Books in St. James’s Library. Framed by a history of the Christian church, A Tale satirized contemporary literary and scholarly pedants as well as

the dissenters and Roman Catholics who opposed the Anglican church, an

institution to which Swift would be devoted during his entire career.

The

Protestant control of England under Oliver Cromwell had resulted in an attempt

by the government to impose the stringent, unpopular beliefs of Puritanism on

the English populace. Swift detested such tyranny and sought to prevent it

through his writings. The

Battle of the Books was

written in defense of Temple. A controversial debate was being waged over the

respective merits of ancient versus modern learning, with Temple supporting the

position that the literature of the Greek and Roman civilizations was far

superior to any modern creations. Swift addressed Temple’s detractors with an

allegorical satire

that depicted the victory of those who supported the ancient texts. Although

inspired by topical controversies, both A Tale and The Battle are brilliant satires with many universal implications regarding

the nature and follies of aesthetics, religious belief, scholasticism, and education.

When

Temple died in 1699, Swift was left without position or prospects. He returned

to Ireland, where he occupied a series of church posts from 1699 to 1710.

During this period he wrote an increasing number of satirical essays on behalf

of the ruling Whig party, whose policies limiting the power of the crown and

increasing that of Parliament, as well as restricting Roman Catholics from

political office, Swift staunchly endorsed. In these pamphlets, Swift developed

the device that marked much of his later satire: using a literary persona to express

ironically absurd opinions. When the Whig administration fell in 1709, Swift

shifted his support to the Tory government, which, while supporting a strong

crown unlike the Whigs, adamantly supported the Anglican Church. For the next

five years, Swift served as the chief Tory political writer, editing the

journal The

Examiner and

composing political pamphlets, poetry, and prose. Swift’s change of party has

led some critics to characterize him as a cynical opportunist, but others

contend that his conversion reflected more of a change in the parties’ philosophies

than in Swift’s own views.

The

‘‘Travells’’ On

August 14, 1725, Jonathan Swift wrote to his friend Charles Ford: ‘‘I have

finished my Travells, and I am now transcribing them; they are admirable Things,

and will wonderfully mend the World.’’ Gulliver’s Travels challenged his readers’ smug assumptions about

the superiority of their political and social institutions as well as their

assurance that as rational animals they occupied a privileged position in the

world. Universally considered Swift’s greatest work of this period, Gulliver’s Travels (published as Travels into

Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts; by Lemuel Gulliver), depicts one man’s journeys to several strange

and unusual lands. Written over a period of several years, some scholars

believe that the novel had its origins during Swift’s years as a political

agitator, when he was part of a group of prominent Tory writers known as the

Scriblerus Club. The group, which included Alexander Pope, John Gay, and John

Arbuthnot, collaborated on several satires, including The Scriblerus Papers. They also planned a satire called The Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus, which was to include several imaginary

voyages. Many believe that Gulliver’s

Travels was

inspired by this work. Although the novel was published anonymously, Swift’s

authorship was widely suspected. The book was an immediate success.

Other

works of literature considered to be exemplars of scathing satire include:

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), a novel by Mark Twain. Told through the eyes of an

innocent abroad, Twain’s greatest novel is an indictment of many entrenched

ideas and prejudices, particularly racism.

Catch-22 (1961), a novel by Joseph Heller. Considered one of the

greatest literary works of the twentieth century, this tale set during World

War II turns nearly every

moral

and logical convention on its head: ‘‘the only way to survive such an insane

system is to be insane oneself.’’

Babbitt (1922), a novel by Sinclair Lewis. Lewis’s first novel, it

quickly earned a place as a classic satire of American culture, particularly

middle-class conformity.

Advent of Middle Class Literature: Defoe, Steele and

Addison

Daniel Defoe: Defoe has been called the father of both

the novel and modern journalism. In his novels, Defoe combined elements of

spiritual autobiography, allegory, and so called ‘‘rogue biography’’ with

stylistic techniques including dialogue, setting, symbolism, characterization,

and, most importantly, irony to fashion some of the first realistic narratives

in English fiction. With this combination, Defoe popularized the novel among a

growing middleclass readership. In journalism, he pioneered the lead article,

investigative reporting, advice and gossip columns, letters to the editor,

human interest features, background articles, and foreign-news analysis.

Persecution, Plague, and Fire: Defoe was born sometime in 1660, the youngest of three children,

to James and Alice Foe in the parish of St. Giles Cripplegate, just north of

the old center of London. The year 1660 also marked the restoration of the

monarchy in England. King Charles I had been executed in 1649, and the British

monarchy was abolished. The English king was considered head of the Anglican Church,

so the execution of Charles I had religious meaning as well.

In 1697

he published his first important work, Essay upon Projects, and four years later made his name known with his long poem The

True-Born Englishman,

his effort to counter a growing English xenophobia, or hatred of foreigners.

This poem, which satirized the prejudices of his fellow countrymen and called

the English a race of mongrels, sold more copies in a single day than any other

poem in English history. It was about this time that Daniel Foe began calling

himself Defoe. In 1702’s The Shortest Way with Dissenters, Defoe wrote

anonymously in the voice of those who would further limit the rights of

Dissenters, exaggerating their positions in an attempt to make them appear

absurd. Unfortunately, Defoe’s satire was grossly misunderstood.

Working

for Secretary of State Robert Harley for a fee of two hundred pounds a year,

Defoe founded the Review

of the Affairs of France, with Observations on Transactions at Home in 1704 and continued writing it for over

nine years. That the paper promoted Harley’s views—pro-Anglican,

anti-Dissenter, against foreign entanglements—did not seem to bother Defoe, who

had the ability to write from different perspectives. He produced the journal

two to three times per week for almost a decade, laying it to rest in June of

1713.

Robinson Crusoe: Defoe’s lasting fame for most readers lies with the book that he

published in 1719, The Life and Strange Surprising

Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, better known to modern readers simply as Robinson Crusoe. Defoe had long been developing the tools

of his trade: point of view, dialogue, characterization, and a sense of scene.

Employing

the form of a travel biography, the work tells the story of a man marooned on a

Caribbean island. He quickly followed it with The Farther

Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1719)

and Serious Reflections during the Life and Surprising

Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1720).

Like all

great creative works, Robinson

Crusoe lends itself

to myriad interpretations: as an allegorical representation of the British

Empire, an attack on economic individualism and capitalism, a further

installment in the author’s spiritual biography, and as a lightly veiled

allegory of Defoe’s own life. Most importantly, however, is the fact that the

novel was read widely by Defoe’s contemporaries in England. It was the first

work to become popular among the middle and even lower classes, who could

identify with Crusoe’s adventures.

1722–1724: In 1722, Defoe published Moll Flanders as well as Journal

of the Plague Year and

Colonel Jack. He was not content, however, with this

achievement, but interspersed the fiction with several nonfiction books of history

and social and religious manners. Another fictional biography, Moll Flanders is told by Moll herself to a rather

embarrassed editor who cleans up her language. In its pages, Defoe was able to

use the criminals and prostitutes he had rubbed shoulders with during his time

in hiding and in jail.

Colonel Jack, another biographical novel, is set in the

underworld of thieves and pickpockets, and traces Jack’s fortunes as he tries

to succeed through honest work. A Fortunate Mistress (1724), better known as Roxana, the last of Defoe’s novels, introduces

Defoe’s first introspective narrator, foreshadowing the psychological novels

that would someday follow. Many critics claim Roxana to

be Defoe’s most complex and artistic work, though it has not retained the same

popularity as has Robinson

Crusoe or Moll Flanders.

A Journal of the

Plague Year is a historical novel set during the London

Plague of 1665 and 1666. The novel is narrated by one ‘‘H. F.,’’ a man likely

modeled on he was born, but he suffered from gout and kidney stones. Defoe died

in hiding on April 26, 1731. Obituaries of the day spoke of Defoe’s varied

writing abilities and his promotion of civic and religious freedom, but none

mentioned that he was the author of either Robinson Crusoe or Moll

Flanders.

Rogue Biography: Not considered quite decent in its day, Moll

Flanders was nonetheless popular with the reading public.

As with Charles Dickens in his novel Oliver Twist, Defoe brings the criminal element vibrantly to life within its

pages. Its form is an extension of what was known as rogue biography. Naturalistic

novels such as E´mile Zola’s Nana (1880)

and Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie (1900) opened up the possibilities of a critical evaluation of Moll

Flanders, just

as the relaxed moral standards of the 1960s made possible the republication of

John Cleland’s Fanny Hill (1749), which was influenced by Defoe’s work.

Precursor to the Gothic Novel: Journal of the

Plague Year developed new fictional ground that would

later be taken over by the gothic novel. Defoe’s prose style conveys a sense of

gripping immediacy; he frequently works with loose sentences that tend to

accumulate in the manner of breathless street gossip and unpremeditated

outcome, thus making his Journal

a compelling work of art that possesses, as

Anthony Burgess has noted, ‘‘the truth of the

conscientious and scrupulous historian, but its deeper truth belongs to the

creative imagination.’’ Along with Robinson Crusoe, Journal

of the Plague Year formed

a model for the exploitation of dramatic and sublime scenes in the novel,

effects that the gothic novel would later borrow to good effect.

Note: Robinson Crusoe is a meditation on the human condition and an argument for

challenging traditional notions about that condition. With this work, Defoe

applied and thereby popularized modern realism. Modern realism holds that truth

should be discovered at the individual level by verification of the senses.

The

following titles represent other modern realist works.

Candide (1759), a novel by Voltaire. This novel

parodies German philosopher Gottfried Leibnitz’s philosophy of optimism, which

states that since God created the world and God is perfect, everything in the

world is ultimately perfect.

Don Quixote (1605), a novel by Miguel de Cervantes. One of the great comic

figures of world literature, drawn with realist and humanist techniques, Don

Quixote is an idealistic but delusionary knight-errant with an illiterate but

loyal squire, Sancho Panza.

Peer Gynt (1867), a play by Henrik Ibsen. This play, originally a long

poem, pokes fun at then-emerging trends about getting back to nature and

simplicity and asks questions about the nature of identity; the main character longs

for freedom in a world that demands commitment.

Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a novel by Jonathan Swift. A political satire in the

form of an adventure, this novel examines the question of rationality being the

greatest human quality, versus humankind’s inborn urge to sin.

Sir Richard Steele: Steele wrote some prose comedies, the best of which are The Funeral (1701), The Lying Lover (1703),

The Tender Husband (1705), and The

Conscious Lovers (1722). They follow in general scheme

the Restoration comedies, but are without the grossness and impudence of their

models. Indeed, Steele's one importance as a dramatist rests on his foundation

of the sentimental comedy, avowedly moral and pious in aim and tone. In places

his plays are lively, and reflect much of Steele's amiability of temper. His Essays. (It

is as a miscellaneous essayist that Steele finds his place in literature.

He was a man fertile in ideas, but he

lacked the application that is always so necessary to carry those ideas to

fruition Thus he often sowed in order that other men might reap. He started The Tatler in

1709, The Spectator in 1711, and several other short-lived periodicals, such as The Guardian (1713),

The Englishman (1713), The

Reader (1714), and The Plebeian (1719).

After the rupture with Addison the loss of the latter's steadying

influence was acutely felt, and nothing that Steele attempted had any

stability.

JOSEPH ADDISON: He

obtained a travelling scholarship of three hundred pounds a year, and saw much

of Europe under favourable conditions. Then the misfortunes of the Whigs in

1703 reduced him to poverty. In 1704, it is said at the instigation of the

leaders of the Whigs, he wrote the poem The

Campaign, praising the war policy of the Whigs in

general and the worthiness of Marlborough in particular. This poem brought him fame and fortune. He obtained many official appointments and pensions, married

a dowager countess (1716), and became a Secretary of State (1717). Two years

later he died, at the early age of forty-seven.

His Drama: Addison was lucky in his greatest dramatic effort, just as

he was lucky in his longest poem. In 1713 he produced the tragedy of Cato, part

of which had been in manuscript as early as 1703. It is of little merit, and

shows that Addison, whatever his other qualities may be, is no dramatist. It is

written in laborious blank verse, in which wooden characters declaim long, dull

speeches. But it caught the ear of the political parties, both of which in the

course of the play saw pithy references to the inflamed passions of the time.

The play had the remarkable run of twenty nights, and was revived with much success.

Addison also attempted an opera, Rosamond

(1707), which was a failure; and the

prose comedy of The Drummer (1715) is said, with some reason, to be his also. If it is,

it adds nothing to his reputation.

His Prose. (several political pamphlets are ascribed to Addison, but

as a pamphleteer he is not impressive. He lacked the directness of Swift, whose

pen was a terror to his opponents. It is in fact almost entirely as an essayist

that Addison is justly famed) (These essays began almost casually. On April 12,

1709, Steele published the first number of The

Tatler, a periodical that was to appear thrice

weekly. Addison, who was a school and college friend of Steele, saw and liked

the new publication, and offered his services as a contributor. His offer was

accepted, and his first contribution, a semi-political one, appeared in No. 18.

Henceforward Addison wrote regularly for the paper, contributing about 42

numbers, which may be compared with Steele's share of about 188. The Tatler finished

in January 1711; then in March of the same year Steele began The Spectator, which

was issued daily.

In March 1713 Addison assisted Steele

with The Guardian, which' Steele began. It was only a moderate success, and

terminated after 175 numbers, Addison contributing 51 In all, we thus have

from Addison's pen nearly four hundred essays, which are of nearly uniform

length, of almost unvarying excellence of style, and of a wide diversity of

subject. They are a faithful reflection of the life of the time viewed with an

aloof and dispassionate observation. He set out to be a mild censor of the

morals of the age, and most of his compositions deal with topical

subjects--fashions, head-dresses, practical jokes, polite conversation. His

aim was to point out "those vices which are too trivial for the chastisement

of the law, and too fantastical for the cognizance of the pulpit.... All agreed

that I should be at liberty to carry the war into what quarters I pleased;

provided I continued to combat with criminals in a body, and to assault the

vice without hurting the person."

Philosophy and Mysticism: Berkeley & Shaftesbury

George Berkeley: Having taken holy orders, he went to London (1713), and

became acquainted with Swift and other wits. He was a man of noble and

charitable mind, and interested himself in many worthy schemes. He was

appointed a dean, and then was made Bishop of Cloyne in 1734. He was a man of

great and enterprising mind, and wrote with much charm on a diversity of

scientific, philosophical, and metaphysical subjects.

Among his books are The Principles of Human Knowledge, a notable effort

in the study of the human mind that appeared in 1710, Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous (1713), and Alciphron,

or The Minute Philosopher (1732). He is

among the first, both in time and in quality, of the English philosophers who

have dressed their ideas in language of literary distinction. He writes with

delightful ease, disdaining ornament or affectation, and his command of gentle

irony is capable and sure.

Anthony Ashley Cooper, third Earl of Shaftesbury, is another

example of the aristocratic dilettante

man of letters. He had little taste for

the politics of the time, and aspired to be famous as a great writer. He

travelled much, and died at Naples in 1713. His books are written with great

care and exactitude, and are pleasant and lucid without being particularly

striking. His Characteristics of Men, Manners,

Opinions, and Times (1711), though it contains nothing very

original or profound, suited the taste of the time and was widely popular.

Poetry: Lady Winchilsea, Watts

Lady Winchilsea (1661-1720). Born in Hampshire, the daughter of Sir William Kingsmill,

Anne, Countess of Winchilsea, passed most of her life in London, where she became

acquainted with Pope and other literary notables. Some of her poems, which were

of importance in their day, are The

Spleen (1701), a Pindaric ode; The Prodigy (1706);

and Miscellany Poems (1713), containing A

Nocturnal Reverie. Wordsworth says, "Now it is

remarkable that, excepting the Nocturnal

Reverie of Lady Winchilsea, and a passage or

two in the Windsor Forest of Pope, the poetry intervening between the publication of

the Paradise Lost and The

Seasons does not contain a single new image of

external nature." This statement is perhaps an exaggeration, but there is no

doubt that Lady Winchilsea had the gift of producing smooth and melodious

verse, and she had a discerning eye for the beauties of nature. They were,

however, the beauties of a garden, rather than those of the wilds.

Isaac Watts (1674–1784): Watts was an English songwriter who penned over

seven hundred hymns. He is popularly known as the "Father of English

Hymnody.”

Doctrinal Classicism: Johnson

Samuel Johnson

(1709-84) Perhaps the best-known and most often-quoted English writer

after William Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson ranks as England’s major literary

figure of the second half of the eighteenth century. He is remembered as a

witty conversationalist who dominated the literary scene of London and the man

immortalized by James Boswell in The Life of Samuel Johnson (1791). He was known in his day as the ‘‘Great Cham (sovereign or

monarch) of Literature.’’

His Life, Johnson has a faithful chronicler in Boswell, whose Life of Samuel Johnson makes us intimate with its subject to a degree rare in

literature. But even the prying zeal of Boswell could not extort many facts

regarding the great man's early life. From the obscure position of a

publisher's hack he became a poet of some note by the publication of London (1738),

which was noticed by Pope; his Dictionary

(1747-55) advanced his fame; then

somewhat incomprehensibly he appears in the limelight as one of the literary

dictators of London, surrounded by a circle of brilliant men.

His Poetry. He wrote little poetry, and none of it, though it has much

merit, can be called first-class. His first poem, London (1738),

written in the heroic couplet, is of great and sombre power. It depicts the

vanities and the sins of city life viewed from the depressing standpoint of an

embittered and penurious poet. His only other longish poem is The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749). The poem, in imitation of the Tenth Satire of Juvenal,

transfers to the activities of mankind in general the gloomy convictions raised

ten years earlier by the spectacle of London.

His Prose. (Johnson's claims to be called a first-rate writer must rest

on his prose. His earliest work appeared in Cave's The Gentleman's Magazine, between the years 1738 and 1744. For this periodical he

wrote (1741-44) imaginary Parliamentary debates, based on the mere skeletons of

facts which he could obtain without attending the House, and elaborated by his

own invention) and embellished with his own vigorous style. In 1744 appeared The Life of Savage, his penurious poet friend, who had recently died in gaol. It

was later incorporated in The Lives

of the Poets and throws much light on Johnson's

early hardships and struggles. Greater schemes were now contemplated, but his

first move towards his edition of Shakespeare came to nothing owing to the

impending appearance of Warburton's edition.

Then, (1747, he began work on his Dictionary of the English Language). This was his greatest contribution to scholarship. It has its

weaknesses: it was a poor guide to pronunciation; the etymology was sometimes inaccurate;

some quotations lacked dates and references; some definitions

were incorrect, some prejudiced, some verbose.

He wrote Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia (1759), in order to pay for his mother's funeral. It was

meant to be a philosophical novel, but it is really a number of Rambler essays,

strung together through the personality of an inquiring young prince called

Rasselas. It is hardly a novel at all; the tale carries little interest, the

characters are rudimentary, and there are many long, dull discussions. In

the book, however, there are many shrewd comments and much of Johnson's sombre

clarity of vision. During this period (1758-60) he was contributing a series of

papers, under the title of The

Idler, to the Universal Chronicle, or Weekly Gazette. They were lighter in touch and shorter than those of The Rambler.

(Then came Johnson's second truly great

work--his fine edition of Shakespeare,

published in 1765. Based on a wide

reading in Elizabethan literature, the edition offered nothing new in the way

of method, but aimed at the restoration of the original, text wherever

possible) and the clearing away of the jungle of fanciful conjecture which had led

to its corruption.

Johnson's Preface to his Shakespeare is a

landmark, not only in Shakespearian scholarship, but in English criticism as a

whole. It established firmly his belief that "there is always an appear

open from criticism to nature."

His A

Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775),

a travel book, shows the faculty of narrative, and contains passages of great

skill. His last work of any consequence was The

Lives of the Poets (1777-81), planned as a series of

introductions to the works of fifty-two poets. In Johnson's hands the

introductions, half biographical, half critical, grew beyond their proposed

size, and they are now regarded as criticism of great and permanent values.)

The poets dealt with are those of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the

period which Johnson found most congenial. He is best when truly in sympathy

with his subject, as in the lives of Dryden and Pope, and, though personal

antipathies distort his judgments of Milton and Gray, there can be no doubt of his

intention to try to be just.

Note:-

Johnson

often used satire to critique modern social and political conditions and to

point out the weaknesses in human nature. Here are some other well-known

satirical works:

Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a novel by Jonathan Swift. This novel satirizes the

foibles of the human condition through a parody of travel writing.

The Devil’s Dictionary (1911), a nonfiction work by Ambrose Bierce. This book gives

reinterpretations of English words and terms that are meant to satirize political

doubletalk.

The Simpsons (1989–), an animated television series created by Matt Groening.

This television show satirizes American culture and society through a parody of

middle-class family life.

Mark Akenside (1721-70). Akenside was born at Newcastle, studied medicine at

Edinburgh, and graduated at Leyden in 1744. He started practice at Northampton,

but did not succeed. Later he had more success in London. He was a well-known

character, and is said to have been caricatured by Smollett in Peregrine Pickle. His

best political poem is his An

Epistle to Curio (1744), which contains some brilliant invective

against Pulteney. His best-known book is The

Pleasures of the Imagination (1744),

a long and rambling blank-verse poem.

Next –

The Age of Transition

The Romantic Age

Sources

English Literature by Edward

Albert [Revised by J. A. Stone]

History of English Literature,

by Legouis and Cazamian

The Routledge History of Literature in English: Britain

and Ireland, by Ronald Carter and John McRae

Gale’s Contextual Encyclopedia of World Literature

Image: Minardia.Wordpress.Com

No comments:

Post a Comment